Reproducible Builds: Reproducible Builds in August 2020

In our monthly reports, we summarise the things that we have been up to over the past month. The motivation behind the Reproducible Builds effort is to ensure no flaws have been introduced from the original free software source code to the pre-compiled binaries we install on our systems. If you re interested in contributing to the project, please visit our main website.

In our monthly reports, we summarise the things that we have been up to over the past month. The motivation behind the Reproducible Builds effort is to ensure no flaws have been introduced from the original free software source code to the pre-compiled binaries we install on our systems. If you re interested in contributing to the project, please visit our main website.

This month, Jennifer Helsby launched a new reproduciblewheels.com website to address the lack of reproducibility of Python wheels. To quote Jennifer s accompanying explanatory blog post:

One hiccup we ve encountered in SecureDrop development is that not all Python wheels can be built reproducibly. We ship multiple (Python) projects in Debian packages, with Python dependencies included in those packages as wheels. In order for our Debian packages to be reproducible, we need that wheel build process to also be reproducibleParallel to this, transparencylog.com was also launched, a service that verifies the contents of URLs against a publicly recorded cryptographic log. It keeps an append-only log of the cryptographic digests of all URLs it has seen. (GitHub repo)

On 18th September, Bernhard M. Wiedemann will give a presentation in German, titled Wie reproducible builds Software sicherer machen ( How reproducible builds make software more secure ) at the Internet Security Digital Days 2020 conference.

On 18th September, Bernhard M. Wiedemann will give a presentation in German, titled Wie reproducible builds Software sicherer machen ( How reproducible builds make software more secure ) at the Internet Security Digital Days 2020 conference.

Reproducible builds at DebConf20

There were a number of talks at the recent online-only DebConf20 conference on the topic of reproducible builds.

Holger gave a talk titled Reproducing Bullseye in practice , focusing on independently verifying that the binaries distributed from

Holger gave a talk titled Reproducing Bullseye in practice , focusing on independently verifying that the binaries distributed from ftp.debian.org are made from their claimed sources. It also served as a general update on the status of reproducible builds within Debian. The video (145 MB) and slides are available.

There were also a number of other talks that involved Reproducible Builds too. For example, the Malayalam language mini-conference had a talk titled , ? ( I want to join Debian, what should I do? ) presented by Praveen Arimbrathodiyil, the Clojure Packaging Team BoF session led by Elana Hashman, as well as Where is Salsa CI right now? that was on the topic of Salsa, the collaborative development server that Debian uses to provide the necessary tools for package maintainers, packaging teams and so on.

Jonathan Bustillos (Jathan) also gave a talk in Spanish titled Un camino verificable desde el origen hasta el binario ( A verifiable path from source to binary ). (Video, 88MB)

There were also a number of other talks that involved Reproducible Builds too. For example, the Malayalam language mini-conference had a talk titled , ? ( I want to join Debian, what should I do? ) presented by Praveen Arimbrathodiyil, the Clojure Packaging Team BoF session led by Elana Hashman, as well as Where is Salsa CI right now? that was on the topic of Salsa, the collaborative development server that Debian uses to provide the necessary tools for package maintainers, packaging teams and so on.

Jonathan Bustillos (Jathan) also gave a talk in Spanish titled Un camino verificable desde el origen hasta el binario ( A verifiable path from source to binary ). (Video, 88MB)

Development work

After many years of development work, the compiler for the Rust programming language now generates reproducible binary code. This generated some general discussion on Reddit on the topic of reproducibility in general.

Paul Spooren posted a request for comments to OpenWrt s

After many years of development work, the compiler for the Rust programming language now generates reproducible binary code. This generated some general discussion on Reddit on the topic of reproducibility in general.

Paul Spooren posted a request for comments to OpenWrt s openwrt-devel mailing list asking for clarification on when to raise the PKG_RELEASE identifier of a package. This is needed in order to successfully perform rebuilds in a reproducible builds context.

In openSUSE, Bernhard M. Wiedemann published his monthly Reproducible Builds status update.

Chris Lamb provided some comments and pointers on an upstream issue regarding the reproducibility of a Snap / SquashFS archive file. [ ]

In openSUSE, Bernhard M. Wiedemann published his monthly Reproducible Builds status update.

Chris Lamb provided some comments and pointers on an upstream issue regarding the reproducibility of a Snap / SquashFS archive file. [ ]

Debian

Holger Levsen identified that a large number of Debian .buildinfo build certificates have been tainted on the official Debian build servers, as these environments have files underneath the /usr/local/sbin directory [ ]. He also filed against bug for debrebuild after spotting that it can fail to download packages from snapshot.debian.org [ ].

This month, several issues were uncovered (or assisted) due to the efforts of reproducible builds.

For instance, Debian bug #968710 was filed by Simon McVittie, which describes a problem with detached debug symbol files (required to generate a traceback) that is unlikely to have been discovered without reproducible builds. In addition, Jelmer Vernooij called attention that the new Debian Janitor tool is using the property of reproducibility (as well as diffoscope when applying archive-wide changes to Debian:

This month, several issues were uncovered (or assisted) due to the efforts of reproducible builds.

For instance, Debian bug #968710 was filed by Simon McVittie, which describes a problem with detached debug symbol files (required to generate a traceback) that is unlikely to have been discovered without reproducible builds. In addition, Jelmer Vernooij called attention that the new Debian Janitor tool is using the property of reproducibility (as well as diffoscope when applying archive-wide changes to Debian:

New merge proposals also include a link to the diffoscope diff between a vanilla build and the build with changes. Unfortunately these can be a bit noisy for packages that are not reproducible yet, due to the difference in build environment between the two builds. [ ]

56 reviews of Debian packages were added, 38 were updated and 24 were removed this month adding to our knowledge about identified issues. Specifically, Chris Lamb added and categorised the nondeterministic_version_generated_by_python_param and the lessc_nondeterministic_keys toolchain issues. [ ][ ]

Holger Levsen sponsored Lukas Puehringer s upload of the python-securesystemslib pacage, which is a dependency of in-toto, a framework to secure the integrity of software supply chains. [ ]

Lastly, Chris Lamb further refined his merge request against the

Holger Levsen sponsored Lukas Puehringer s upload of the python-securesystemslib pacage, which is a dependency of in-toto, a framework to secure the integrity of software supply chains. [ ]

Lastly, Chris Lamb further refined his merge request against the debian-installer component to allow all arguments from sources.list files (such as [check-valid-until=no]) in order that we can test the reproducibility of the installer images on the Reproducible Builds own testing infrastructure and sent a ping to the team that maintains that code.

Upstream patches

The Reproducible Builds project detects, dissects and attempts to fix as many currently-unreproducible packages as possible. We endeavour to send all of our patches upstream where appropriate. This month, we wrote a large number of these patches, including:

-

Bernhard M. Wiedemann:

asymptote (shell/Perl date)getfem (embeds datetime and user, submitted via email)getdp (hostname and user)getdp (user)guix (disable parallelism)httpcomponents-client (Java documentation generator readdir order)kuberlr (date)lal (date and time issue, submitted via email)libmesh (host)OBS (discuss how to track old build prjconf metadata in buildinfo)openblas (disable CPU detection)openfoam-selector (date)perl (toolchain, date)python-blosc (CPU detection)python-eventlet (fails to build far in the future)rna-star (date and hostname)trilinos (date)xz/b4 (workaround CPU count influencing output, reported upstream)

-

Benjamin Hof:

-

Chris Lamb:

- #966657 filed against

json-c (forwarded upstream).

- #967238 filed against

nmh.

- #968045 filed against

golang-gonum-v1-plot.

- #968183 filed against

chirp.

- #968185 filed against

pixelmed-codec.

- #968187 filed against

debhelper.

- #968189 filed against

muroar.

- #968278 filed against

serd.

- #968344 filed against

pencil2d.

- #968557 filed against

tpot.

- #968700 filed against

evolution.

- #969320 filed against

aflplusplus.

-

Herv Boutemy:

plexus-archiver (timezone/DST issue)

-

Vagrant Cascadian:

- #968627 filed against

libjpeg-turbo.

- #968641 filed against

jack-audio-connection-kit.

- #968652 filed against

glusterfs.

diffoscope

diffoscope is our in-depth and content-aware diff utility that can not only locate and diagnose reproducibility issues, it provides human-readable diffs of all kinds. In August, Chris Lamb made the following changes to diffoscope, including preparing and uploading versions

diffoscope is our in-depth and content-aware diff utility that can not only locate and diagnose reproducibility issues, it provides human-readable diffs of all kinds. In August, Chris Lamb made the following changes to diffoscope, including preparing and uploading versions 155, 156, 157 and 158 to Debian:

-

New features:

-

Bug fixes:

- Don t raise an exception when we encounter XML files with

<!ENTITY> declarations inside the Document Type Definition (DTD), or when a DTD or entity references an external resource. (#212)

pgpdump(1) can successfully parse some binary files, so check that the parsed output contains something sensible before accepting it. [ ]- Temporarily drop

gnumeric from the Debian build-dependencies as it has been removed from the testing distribution. (#968742)

- Correctly use

fallback_recognises to prevent matching .xsb binary XML files.

- Correct identify signed PGP files as

file(1) returns data . (#211)

-

Logging improvements:

- Emit a message when

ppudump version does not match our file header. [ ]

- Don t use Python s

repr(object) output in Calling external command messages. [ ]

- Include the filename in the not identified by any comparator message. [ ]

-

Codebase improvements:

- Bump Python requirement from 3.6 to 3.7. Most distributions are either shipping with Python 3.5 or 3.7, so supporting 3.6 is not only somewhat unnecessary but also cumbersome to test locally. [ ]

- Drop some unused imports [ ], drop an unnecessary dictionary comprehensions [ ] and some unnecessary control flow [ ].

- Correct typo of output in a comment. [ ]

-

Release process:

-

Testsuite improvements:

- Update PPU tests for compatibility with Free Pascal versions 3.2.0 or greater. (#968124)

- Mark that our identification test for

.ppu files requires ppudump version 3.2.0 or higher. [ ]

- Add an assert_diff helper that loads and compares a fixture output. [ ][ ][ ][ ]

-

Misc:

- Duplicate docker instructions in the Get diffoscope section of the diffoscope website. [ ]

In addition, Mattia Rizzolo documented in setup.py that diffoscope works with Python version 3.8 [ ] and Frazer Clews applied some Pylint suggestions [ ] and removed some deprecated methods [ ].

Website

This month, Chris Lamb updated the main Reproducible Builds website and documentation to:

This month, Chris Lamb updated the main Reproducible Builds website and documentation to:

- Clarify & fix a few entries on the who page [ ][ ] and ensure that images do not get to large on some viewports [ ].

- Clarify use of a pronoun re. Conservancy. [ ]

- Use View all our monthly reports over View all monthly reports . [ ]

- Move a is a suffix out of the link target on the

SOURCE_DATE_EPOCH age. [ ]

In addition, Javier Jard n added the freedesktop-sdk project [ ] and Kushal Das added SecureDrop project [ ] to our projects page. Lastly, Michael P hn added internationalisation and translation support with help from Hans-Christoph Steiner [ ].

Testing framework

The Reproducible Builds project operate a Jenkins-based testing framework to power

The Reproducible Builds project operate a Jenkins-based testing framework to power tests.reproducible-builds.org. This month, Holger Levsen made the following changes:

-

System health checks:

- Improve explanation how the status and scores are calculated. [ ][ ]

- Update and condense view of detected issues. [ ][ ]

- Query the canonical configuration file to determine whether a job is disabled instead of duplicating/hardcoding this. [ ]

- Detect several problems when updating the status of reporting-oriented metapackage sets. [ ]

- Detect when diffoscope is not installable [ ] and failures in DNS resolution [ ].

-

Debian:

- Update the URL to the Debian security team bug tracker s Git repository. [ ]

- Reschedule the unstable and bullseye distributions often for the

arm64 architecture. [ ]

- Schedule buster less often for

armhf. [ ][ ][ ]

- Force the build of certain packages in the work-in-progress package rebuilder. [ ][ ]

- Only update the stretch and buster base build images when necessary. [ ]

-

Other distributions:

-

Misc;

- Improve monitoring, such as number of mounts, disk, memory, etc.. [ ][ ][ ][ ]

- Install the

ruby-jekyll-polyglot package to needed for the recently-added internationalisation and translation support on the Reproducible Builds website. [ ]

- Update link to report potential issues. [ ][ ]

Many other changes were made too, including:

-

Chris Lamb:

-

Mattia Rizzolo:

- For Alpine and ArchLinux, make the cleanup routines in the event of an error more robust. [ ]

- Update the sudo configuration to permit Jenkins itself to unmount more directories. [ ]

- Setup automatic renewal of our Let s Encrypt certificates for all domains served by us (including

jenkins.debian.net, www.reproducible-builds.org, diffoscope.org, buildinfos.debian.net, etc.). [ ][ ][ ][ ][ ]

-

Vagrant Cascadian:

- Mark that the u-boot Universal Boot Loader should not build architecture independent packages on the

arm64 architecture anymore. [ ]

Finally, build node maintenance was performed by Holger Levsen [ ], Mattia Rizzolo [ ][ ] and Vagrant Cascadian [ ][ ][ ][ ]

Mailing list

On our mailing list this month, Leo Wandersleb sent a message to the list after he was wondering how to expand his WalletScrutiny.com project (which aims to improve the security of Bitcoin wallets) from Android wallets to also monitor Linux wallets as well:

If you think you know how to spread the word about reproducibility in the context of Bitcoin wallets through WalletScrutiny, your contributions are highly welcome on this PR [ ]

Julien Lepiller posted to the list linking to a blog post by Tavis Ormandy titled You don t need reproducible builds. Morten Linderud (foxboron) responded with a clear rebuttal that Tavis was only considering the narrow use-case of proprietary vendors and closed-source software. He additionally noted that the criticism that reproducible builds cannot prevent against backdoors being deliberately introduced into the upstream source ( bugdoors ) are decidedly (and deliberately) outside the scope of reproducible builds to begin with.

Chris Lamb included the Reproducible Builds mailing list in a wider discussion regarding a tentative proposal to include .buildinfo files in .deb packages, adding his remarks regarding requiring a custom tool in order to determine whether generated build artifacts are identical in a reproducible context. [ ]

Jonathan Bustillos (Jathan) posted a quick email to the list requesting whether there was a list of To do tasks in Reproducible Builds.

Lastly, Chris Lamb responded at length to a query regarding the status of reproducible builds for Debian ISO or installation images. He noted that most of the technical work has been performed but there are at least four issues until they can be generally advertised as such . He pointed that the privacy-oriented Tails operation system, which is based directly on Debian, has had reproducible builds for a number of years now. [ ]

Lastly, Chris Lamb responded at length to a query regarding the status of reproducible builds for Debian ISO or installation images. He noted that most of the technical work has been performed but there are at least four issues until they can be generally advertised as such . He pointed that the privacy-oriented Tails operation system, which is based directly on Debian, has had reproducible builds for a number of years now. [ ]

If you are interested in contributing to the Reproducible Builds project, please visit our Contribute page on our website. However, you can get in touch with us via:

-

IRC:

#reproducible-builds on irc.oftc.net.

-

Twitter: @ReproBuilds

-

Mastodon: @reproducible_builds@fosstodon.org

-

Mailing list:

rb-general@lists.reproducible-builds.org

After many years of development work, the compiler for the Rust programming language now generates reproducible binary code. This generated some general discussion on Reddit on the topic of reproducibility in general.

Paul Spooren posted a request for comments to OpenWrt s

After many years of development work, the compiler for the Rust programming language now generates reproducible binary code. This generated some general discussion on Reddit on the topic of reproducibility in general.

Paul Spooren posted a request for comments to OpenWrt s openwrt-devel mailing list asking for clarification on when to raise the PKG_RELEASE identifier of a package. This is needed in order to successfully perform rebuilds in a reproducible builds context.

In openSUSE, Bernhard M. Wiedemann published his monthly Reproducible Builds status update.

Chris Lamb provided some comments and pointers on an upstream issue regarding the reproducibility of a Snap / SquashFS archive file. [ ]

In openSUSE, Bernhard M. Wiedemann published his monthly Reproducible Builds status update.

Chris Lamb provided some comments and pointers on an upstream issue regarding the reproducibility of a Snap / SquashFS archive file. [ ]

Debian

Holger Levsen identified that a large number of Debian .buildinfo build certificates have been tainted on the official Debian build servers, as these environments have files underneath the /usr/local/sbin directory [ ]. He also filed against bug for debrebuild after spotting that it can fail to download packages from snapshot.debian.org [ ].

This month, several issues were uncovered (or assisted) due to the efforts of reproducible builds.

For instance, Debian bug #968710 was filed by Simon McVittie, which describes a problem with detached debug symbol files (required to generate a traceback) that is unlikely to have been discovered without reproducible builds. In addition, Jelmer Vernooij called attention that the new Debian Janitor tool is using the property of reproducibility (as well as diffoscope when applying archive-wide changes to Debian:

This month, several issues were uncovered (or assisted) due to the efforts of reproducible builds.

For instance, Debian bug #968710 was filed by Simon McVittie, which describes a problem with detached debug symbol files (required to generate a traceback) that is unlikely to have been discovered without reproducible builds. In addition, Jelmer Vernooij called attention that the new Debian Janitor tool is using the property of reproducibility (as well as diffoscope when applying archive-wide changes to Debian:

New merge proposals also include a link to the diffoscope diff between a vanilla build and the build with changes. Unfortunately these can be a bit noisy for packages that are not reproducible yet, due to the difference in build environment between the two builds. [ ]

56 reviews of Debian packages were added, 38 were updated and 24 were removed this month adding to our knowledge about identified issues. Specifically, Chris Lamb added and categorised the nondeterministic_version_generated_by_python_param and the lessc_nondeterministic_keys toolchain issues. [ ][ ]

Holger Levsen sponsored Lukas Puehringer s upload of the python-securesystemslib pacage, which is a dependency of in-toto, a framework to secure the integrity of software supply chains. [ ]

Lastly, Chris Lamb further refined his merge request against the

Holger Levsen sponsored Lukas Puehringer s upload of the python-securesystemslib pacage, which is a dependency of in-toto, a framework to secure the integrity of software supply chains. [ ]

Lastly, Chris Lamb further refined his merge request against the debian-installer component to allow all arguments from sources.list files (such as [check-valid-until=no]) in order that we can test the reproducibility of the installer images on the Reproducible Builds own testing infrastructure and sent a ping to the team that maintains that code.

Upstream patches

The Reproducible Builds project detects, dissects and attempts to fix as many currently-unreproducible packages as possible. We endeavour to send all of our patches upstream where appropriate. This month, we wrote a large number of these patches, including:

-

Bernhard M. Wiedemann:

asymptote (shell/Perl date)getfem (embeds datetime and user, submitted via email)getdp (hostname and user)getdp (user)guix (disable parallelism)httpcomponents-client (Java documentation generator readdir order)kuberlr (date)lal (date and time issue, submitted via email)libmesh (host)OBS (discuss how to track old build prjconf metadata in buildinfo)openblas (disable CPU detection)openfoam-selector (date)perl (toolchain, date)python-blosc (CPU detection)python-eventlet (fails to build far in the future)rna-star (date and hostname)trilinos (date)xz/b4 (workaround CPU count influencing output, reported upstream)

-

Benjamin Hof:

-

Chris Lamb:

- #966657 filed against

json-c (forwarded upstream).

- #967238 filed against

nmh.

- #968045 filed against

golang-gonum-v1-plot.

- #968183 filed against

chirp.

- #968185 filed against

pixelmed-codec.

- #968187 filed against

debhelper.

- #968189 filed against

muroar.

- #968278 filed against

serd.

- #968344 filed against

pencil2d.

- #968557 filed against

tpot.

- #968700 filed against

evolution.

- #969320 filed against

aflplusplus.

-

Herv Boutemy:

plexus-archiver (timezone/DST issue)

-

Vagrant Cascadian:

- #968627 filed against

libjpeg-turbo.

- #968641 filed against

jack-audio-connection-kit.

- #968652 filed against

glusterfs.

diffoscope

diffoscope is our in-depth and content-aware diff utility that can not only locate and diagnose reproducibility issues, it provides human-readable diffs of all kinds. In August, Chris Lamb made the following changes to diffoscope, including preparing and uploading versions

diffoscope is our in-depth and content-aware diff utility that can not only locate and diagnose reproducibility issues, it provides human-readable diffs of all kinds. In August, Chris Lamb made the following changes to diffoscope, including preparing and uploading versions 155, 156, 157 and 158 to Debian:

-

New features:

-

Bug fixes:

- Don t raise an exception when we encounter XML files with

<!ENTITY> declarations inside the Document Type Definition (DTD), or when a DTD or entity references an external resource. (#212)

pgpdump(1) can successfully parse some binary files, so check that the parsed output contains something sensible before accepting it. [ ]- Temporarily drop

gnumeric from the Debian build-dependencies as it has been removed from the testing distribution. (#968742)

- Correctly use

fallback_recognises to prevent matching .xsb binary XML files.

- Correct identify signed PGP files as

file(1) returns data . (#211)

-

Logging improvements:

- Emit a message when

ppudump version does not match our file header. [ ]

- Don t use Python s

repr(object) output in Calling external command messages. [ ]

- Include the filename in the not identified by any comparator message. [ ]

-

Codebase improvements:

- Bump Python requirement from 3.6 to 3.7. Most distributions are either shipping with Python 3.5 or 3.7, so supporting 3.6 is not only somewhat unnecessary but also cumbersome to test locally. [ ]

- Drop some unused imports [ ], drop an unnecessary dictionary comprehensions [ ] and some unnecessary control flow [ ].

- Correct typo of output in a comment. [ ]

-

Release process:

-

Testsuite improvements:

- Update PPU tests for compatibility with Free Pascal versions 3.2.0 or greater. (#968124)

- Mark that our identification test for

.ppu files requires ppudump version 3.2.0 or higher. [ ]

- Add an assert_diff helper that loads and compares a fixture output. [ ][ ][ ][ ]

-

Misc:

- Duplicate docker instructions in the Get diffoscope section of the diffoscope website. [ ]

In addition, Mattia Rizzolo documented in setup.py that diffoscope works with Python version 3.8 [ ] and Frazer Clews applied some Pylint suggestions [ ] and removed some deprecated methods [ ].

Website

This month, Chris Lamb updated the main Reproducible Builds website and documentation to:

This month, Chris Lamb updated the main Reproducible Builds website and documentation to:

- Clarify & fix a few entries on the who page [ ][ ] and ensure that images do not get to large on some viewports [ ].

- Clarify use of a pronoun re. Conservancy. [ ]

- Use View all our monthly reports over View all monthly reports . [ ]

- Move a is a suffix out of the link target on the

SOURCE_DATE_EPOCH age. [ ]

In addition, Javier Jard n added the freedesktop-sdk project [ ] and Kushal Das added SecureDrop project [ ] to our projects page. Lastly, Michael P hn added internationalisation and translation support with help from Hans-Christoph Steiner [ ].

Testing framework

The Reproducible Builds project operate a Jenkins-based testing framework to power

The Reproducible Builds project operate a Jenkins-based testing framework to power tests.reproducible-builds.org. This month, Holger Levsen made the following changes:

-

System health checks:

- Improve explanation how the status and scores are calculated. [ ][ ]

- Update and condense view of detected issues. [ ][ ]

- Query the canonical configuration file to determine whether a job is disabled instead of duplicating/hardcoding this. [ ]

- Detect several problems when updating the status of reporting-oriented metapackage sets. [ ]

- Detect when diffoscope is not installable [ ] and failures in DNS resolution [ ].

-

Debian:

- Update the URL to the Debian security team bug tracker s Git repository. [ ]

- Reschedule the unstable and bullseye distributions often for the

arm64 architecture. [ ]

- Schedule buster less often for

armhf. [ ][ ][ ]

- Force the build of certain packages in the work-in-progress package rebuilder. [ ][ ]

- Only update the stretch and buster base build images when necessary. [ ]

-

Other distributions:

-

Misc;

- Improve monitoring, such as number of mounts, disk, memory, etc.. [ ][ ][ ][ ]

- Install the

ruby-jekyll-polyglot package to needed for the recently-added internationalisation and translation support on the Reproducible Builds website. [ ]

- Update link to report potential issues. [ ][ ]

Many other changes were made too, including:

-

Chris Lamb:

-

Mattia Rizzolo:

- For Alpine and ArchLinux, make the cleanup routines in the event of an error more robust. [ ]

- Update the sudo configuration to permit Jenkins itself to unmount more directories. [ ]

- Setup automatic renewal of our Let s Encrypt certificates for all domains served by us (including

jenkins.debian.net, www.reproducible-builds.org, diffoscope.org, buildinfos.debian.net, etc.). [ ][ ][ ][ ][ ]

-

Vagrant Cascadian:

- Mark that the u-boot Universal Boot Loader should not build architecture independent packages on the

arm64 architecture anymore. [ ]

Finally, build node maintenance was performed by Holger Levsen [ ], Mattia Rizzolo [ ][ ] and Vagrant Cascadian [ ][ ][ ][ ]

Mailing list

On our mailing list this month, Leo Wandersleb sent a message to the list after he was wondering how to expand his WalletScrutiny.com project (which aims to improve the security of Bitcoin wallets) from Android wallets to also monitor Linux wallets as well:

If you think you know how to spread the word about reproducibility in the context of Bitcoin wallets through WalletScrutiny, your contributions are highly welcome on this PR [ ]

Julien Lepiller posted to the list linking to a blog post by Tavis Ormandy titled You don t need reproducible builds. Morten Linderud (foxboron) responded with a clear rebuttal that Tavis was only considering the narrow use-case of proprietary vendors and closed-source software. He additionally noted that the criticism that reproducible builds cannot prevent against backdoors being deliberately introduced into the upstream source ( bugdoors ) are decidedly (and deliberately) outside the scope of reproducible builds to begin with.

Chris Lamb included the Reproducible Builds mailing list in a wider discussion regarding a tentative proposal to include .buildinfo files in .deb packages, adding his remarks regarding requiring a custom tool in order to determine whether generated build artifacts are identical in a reproducible context. [ ]

Jonathan Bustillos (Jathan) posted a quick email to the list requesting whether there was a list of To do tasks in Reproducible Builds.

Lastly, Chris Lamb responded at length to a query regarding the status of reproducible builds for Debian ISO or installation images. He noted that most of the technical work has been performed but there are at least four issues until they can be generally advertised as such . He pointed that the privacy-oriented Tails operation system, which is based directly on Debian, has had reproducible builds for a number of years now. [ ]

Lastly, Chris Lamb responded at length to a query regarding the status of reproducible builds for Debian ISO or installation images. He noted that most of the technical work has been performed but there are at least four issues until they can be generally advertised as such . He pointed that the privacy-oriented Tails operation system, which is based directly on Debian, has had reproducible builds for a number of years now. [ ]

If you are interested in contributing to the Reproducible Builds project, please visit our Contribute page on our website. However, you can get in touch with us via:

-

IRC:

#reproducible-builds on irc.oftc.net.

-

Twitter: @ReproBuilds

-

Mastodon: @reproducible_builds@fosstodon.org

-

Mailing list:

rb-general@lists.reproducible-builds.org

-

Bernhard M. Wiedemann:

asymptote(shell/Perl date)getfem(embeds datetime and user, submitted via email)getdp(hostname and user)getdp(user)guix(disable parallelism)httpcomponents-client(Java documentation generatorreaddirorder)kuberlr(date)lal(date and time issue, submitted via email)libmesh(host)OBS(discuss how to track old buildprjconfmetadata in buildinfo)openblas(disable CPU detection)openfoam-selector(date)perl(toolchain, date)python-blosc(CPU detection)python-eventlet(fails to build far in the future)rna-star(date and hostname)trilinos(date)xz/b4(workaround CPU count influencing output, reported upstream)

- Benjamin Hof:

-

Chris Lamb:

- #966657 filed against

json-c(forwarded upstream). - #967238 filed against

nmh. - #968045 filed against

golang-gonum-v1-plot. - #968183 filed against

chirp. - #968185 filed against

pixelmed-codec. - #968187 filed against

debhelper. - #968189 filed against

muroar. - #968278 filed against

serd. - #968344 filed against

pencil2d. - #968557 filed against

tpot. - #968700 filed against

evolution. - #969320 filed against

aflplusplus.

- #966657 filed against

-

Herv Boutemy:

plexus-archiver(timezone/DST issue)

-

Vagrant Cascadian:

- #968627 filed against

libjpeg-turbo. - #968641 filed against

jack-audio-connection-kit. - #968652 filed against

glusterfs.

- #968627 filed against

diffoscope

diffoscope is our in-depth and content-aware diff utility that can not only locate and diagnose reproducibility issues, it provides human-readable diffs of all kinds. In August, Chris Lamb made the following changes to diffoscope, including preparing and uploading versions

diffoscope is our in-depth and content-aware diff utility that can not only locate and diagnose reproducibility issues, it provides human-readable diffs of all kinds. In August, Chris Lamb made the following changes to diffoscope, including preparing and uploading versions 155, 156, 157 and 158 to Debian:

-

New features:

-

Bug fixes:

- Don t raise an exception when we encounter XML files with

<!ENTITY> declarations inside the Document Type Definition (DTD), or when a DTD or entity references an external resource. (#212)

pgpdump(1) can successfully parse some binary files, so check that the parsed output contains something sensible before accepting it. [ ]- Temporarily drop

gnumeric from the Debian build-dependencies as it has been removed from the testing distribution. (#968742)

- Correctly use

fallback_recognises to prevent matching .xsb binary XML files.

- Correct identify signed PGP files as

file(1) returns data . (#211)

-

Logging improvements:

- Emit a message when

ppudump version does not match our file header. [ ]

- Don t use Python s

repr(object) output in Calling external command messages. [ ]

- Include the filename in the not identified by any comparator message. [ ]

-

Codebase improvements:

- Bump Python requirement from 3.6 to 3.7. Most distributions are either shipping with Python 3.5 or 3.7, so supporting 3.6 is not only somewhat unnecessary but also cumbersome to test locally. [ ]

- Drop some unused imports [ ], drop an unnecessary dictionary comprehensions [ ] and some unnecessary control flow [ ].

- Correct typo of output in a comment. [ ]

-

Release process:

-

Testsuite improvements:

- Update PPU tests for compatibility with Free Pascal versions 3.2.0 or greater. (#968124)

- Mark that our identification test for

.ppu files requires ppudump version 3.2.0 or higher. [ ]

- Add an assert_diff helper that loads and compares a fixture output. [ ][ ][ ][ ]

-

Misc:

- Duplicate docker instructions in the Get diffoscope section of the diffoscope website. [ ]

In addition, Mattia Rizzolo documented in setup.py that diffoscope works with Python version 3.8 [ ] and Frazer Clews applied some Pylint suggestions [ ] and removed some deprecated methods [ ].

Website

This month, Chris Lamb updated the main Reproducible Builds website and documentation to:

This month, Chris Lamb updated the main Reproducible Builds website and documentation to:

- Clarify & fix a few entries on the who page [ ][ ] and ensure that images do not get to large on some viewports [ ].

- Clarify use of a pronoun re. Conservancy. [ ]

- Use View all our monthly reports over View all monthly reports . [ ]

- Move a is a suffix out of the link target on the

SOURCE_DATE_EPOCH age. [ ]

In addition, Javier Jard n added the freedesktop-sdk project [ ] and Kushal Das added SecureDrop project [ ] to our projects page. Lastly, Michael P hn added internationalisation and translation support with help from Hans-Christoph Steiner [ ].

Testing framework

The Reproducible Builds project operate a Jenkins-based testing framework to power

The Reproducible Builds project operate a Jenkins-based testing framework to power tests.reproducible-builds.org. This month, Holger Levsen made the following changes:

-

System health checks:

- Improve explanation how the status and scores are calculated. [ ][ ]

- Update and condense view of detected issues. [ ][ ]

- Query the canonical configuration file to determine whether a job is disabled instead of duplicating/hardcoding this. [ ]

- Detect several problems when updating the status of reporting-oriented metapackage sets. [ ]

- Detect when diffoscope is not installable [ ] and failures in DNS resolution [ ].

-

Debian:

- Update the URL to the Debian security team bug tracker s Git repository. [ ]

- Reschedule the unstable and bullseye distributions often for the

arm64 architecture. [ ]

- Schedule buster less often for

armhf. [ ][ ][ ]

- Force the build of certain packages in the work-in-progress package rebuilder. [ ][ ]

- Only update the stretch and buster base build images when necessary. [ ]

-

Other distributions:

-

Misc;

- Improve monitoring, such as number of mounts, disk, memory, etc.. [ ][ ][ ][ ]

- Install the

ruby-jekyll-polyglot package to needed for the recently-added internationalisation and translation support on the Reproducible Builds website. [ ]

- Update link to report potential issues. [ ][ ]

Many other changes were made too, including:

-

Chris Lamb:

-

Mattia Rizzolo:

- For Alpine and ArchLinux, make the cleanup routines in the event of an error more robust. [ ]

- Update the sudo configuration to permit Jenkins itself to unmount more directories. [ ]

- Setup automatic renewal of our Let s Encrypt certificates for all domains served by us (including

jenkins.debian.net, www.reproducible-builds.org, diffoscope.org, buildinfos.debian.net, etc.). [ ][ ][ ][ ][ ]

-

Vagrant Cascadian:

- Mark that the u-boot Universal Boot Loader should not build architecture independent packages on the

arm64 architecture anymore. [ ]

Finally, build node maintenance was performed by Holger Levsen [ ], Mattia Rizzolo [ ][ ] and Vagrant Cascadian [ ][ ][ ][ ]

Mailing list

On our mailing list this month, Leo Wandersleb sent a message to the list after he was wondering how to expand his WalletScrutiny.com project (which aims to improve the security of Bitcoin wallets) from Android wallets to also monitor Linux wallets as well:

If you think you know how to spread the word about reproducibility in the context of Bitcoin wallets through WalletScrutiny, your contributions are highly welcome on this PR [ ]

Julien Lepiller posted to the list linking to a blog post by Tavis Ormandy titled You don t need reproducible builds. Morten Linderud (foxboron) responded with a clear rebuttal that Tavis was only considering the narrow use-case of proprietary vendors and closed-source software. He additionally noted that the criticism that reproducible builds cannot prevent against backdoors being deliberately introduced into the upstream source ( bugdoors ) are decidedly (and deliberately) outside the scope of reproducible builds to begin with.

Chris Lamb included the Reproducible Builds mailing list in a wider discussion regarding a tentative proposal to include .buildinfo files in .deb packages, adding his remarks regarding requiring a custom tool in order to determine whether generated build artifacts are identical in a reproducible context. [ ]

Jonathan Bustillos (Jathan) posted a quick email to the list requesting whether there was a list of To do tasks in Reproducible Builds.

Lastly, Chris Lamb responded at length to a query regarding the status of reproducible builds for Debian ISO or installation images. He noted that most of the technical work has been performed but there are at least four issues until they can be generally advertised as such . He pointed that the privacy-oriented Tails operation system, which is based directly on Debian, has had reproducible builds for a number of years now. [ ]

Lastly, Chris Lamb responded at length to a query regarding the status of reproducible builds for Debian ISO or installation images. He noted that most of the technical work has been performed but there are at least four issues until they can be generally advertised as such . He pointed that the privacy-oriented Tails operation system, which is based directly on Debian, has had reproducible builds for a number of years now. [ ]

If you are interested in contributing to the Reproducible Builds project, please visit our Contribute page on our website. However, you can get in touch with us via:

-

IRC:

#reproducible-builds on irc.oftc.net.

-

Twitter: @ReproBuilds

-

Mastodon: @reproducible_builds@fosstodon.org

-

Mailing list:

rb-general@lists.reproducible-builds.org

- Don t raise an exception when we encounter XML files with

<!ENTITY>declarations inside the Document Type Definition (DTD), or when a DTD or entity references an external resource. (#212) pgpdump(1)can successfully parse some binary files, so check that the parsed output contains something sensible before accepting it. [ ]- Temporarily drop

gnumericfrom the Debian build-dependencies as it has been removed from the testing distribution. (#968742) - Correctly use

fallback_recognisesto prevent matching.xsbbinary XML files. - Correct identify signed PGP files as

file(1)returnsdata. (#211)

- Emit a message when

ppudumpversion does not match our file header. [ ] - Don t use Python s

repr(object)output in Calling external command messages. [ ] - Include the filename in the not identified by any comparator message. [ ]

- Bump Python requirement from 3.6 to 3.7. Most distributions are either shipping with Python 3.5 or 3.7, so supporting 3.6 is not only somewhat unnecessary but also cumbersome to test locally. [ ]

- Drop some unused imports [ ], drop an unnecessary dictionary comprehensions [ ] and some unnecessary control flow [ ].

- Correct typo of output in a comment. [ ]

- Update PPU tests for compatibility with Free Pascal versions 3.2.0 or greater. (#968124)

- Mark that our identification test for

.ppufiles requiresppudumpversion 3.2.0 or higher. [ ] - Add an assert_diff helper that loads and compares a fixture output. [ ][ ][ ][ ]

- Duplicate docker instructions in the Get diffoscope section of the diffoscope website. [ ]

This month, Chris Lamb updated the main Reproducible Builds website and documentation to:

This month, Chris Lamb updated the main Reproducible Builds website and documentation to:

- Clarify & fix a few entries on the who page [ ][ ] and ensure that images do not get to large on some viewports [ ].

- Clarify use of a pronoun re. Conservancy. [ ]

- Use View all our monthly reports over View all monthly reports . [ ]

- Move a is a suffix out of the link target on the

SOURCE_DATE_EPOCHage. [ ]

Testing framework

The Reproducible Builds project operate a Jenkins-based testing framework to power

The Reproducible Builds project operate a Jenkins-based testing framework to power tests.reproducible-builds.org. This month, Holger Levsen made the following changes:

-

System health checks:

- Improve explanation how the status and scores are calculated. [ ][ ]

- Update and condense view of detected issues. [ ][ ]

- Query the canonical configuration file to determine whether a job is disabled instead of duplicating/hardcoding this. [ ]

- Detect several problems when updating the status of reporting-oriented metapackage sets. [ ]

- Detect when diffoscope is not installable [ ] and failures in DNS resolution [ ].

-

Debian:

- Update the URL to the Debian security team bug tracker s Git repository. [ ]

- Reschedule the unstable and bullseye distributions often for the

arm64 architecture. [ ]

- Schedule buster less often for

armhf. [ ][ ][ ]

- Force the build of certain packages in the work-in-progress package rebuilder. [ ][ ]

- Only update the stretch and buster base build images when necessary. [ ]

-

Other distributions:

-

Misc;

- Improve monitoring, such as number of mounts, disk, memory, etc.. [ ][ ][ ][ ]

- Install the

ruby-jekyll-polyglot package to needed for the recently-added internationalisation and translation support on the Reproducible Builds website. [ ]

- Update link to report potential issues. [ ][ ]

Many other changes were made too, including:

-

Chris Lamb:

-

Mattia Rizzolo:

- For Alpine and ArchLinux, make the cleanup routines in the event of an error more robust. [ ]

- Update the sudo configuration to permit Jenkins itself to unmount more directories. [ ]

- Setup automatic renewal of our Let s Encrypt certificates for all domains served by us (including

jenkins.debian.net, www.reproducible-builds.org, diffoscope.org, buildinfos.debian.net, etc.). [ ][ ][ ][ ][ ]

-

Vagrant Cascadian:

- Mark that the u-boot Universal Boot Loader should not build architecture independent packages on the

arm64 architecture anymore. [ ]

Finally, build node maintenance was performed by Holger Levsen [ ], Mattia Rizzolo [ ][ ] and Vagrant Cascadian [ ][ ][ ][ ]

Mailing list

On our mailing list this month, Leo Wandersleb sent a message to the list after he was wondering how to expand his WalletScrutiny.com project (which aims to improve the security of Bitcoin wallets) from Android wallets to also monitor Linux wallets as well:

If you think you know how to spread the word about reproducibility in the context of Bitcoin wallets through WalletScrutiny, your contributions are highly welcome on this PR [ ]

Julien Lepiller posted to the list linking to a blog post by Tavis Ormandy titled You don t need reproducible builds. Morten Linderud (foxboron) responded with a clear rebuttal that Tavis was only considering the narrow use-case of proprietary vendors and closed-source software. He additionally noted that the criticism that reproducible builds cannot prevent against backdoors being deliberately introduced into the upstream source ( bugdoors ) are decidedly (and deliberately) outside the scope of reproducible builds to begin with.

Chris Lamb included the Reproducible Builds mailing list in a wider discussion regarding a tentative proposal to include .buildinfo files in .deb packages, adding his remarks regarding requiring a custom tool in order to determine whether generated build artifacts are identical in a reproducible context. [ ]

Jonathan Bustillos (Jathan) posted a quick email to the list requesting whether there was a list of To do tasks in Reproducible Builds.

Lastly, Chris Lamb responded at length to a query regarding the status of reproducible builds for Debian ISO or installation images. He noted that most of the technical work has been performed but there are at least four issues until they can be generally advertised as such . He pointed that the privacy-oriented Tails operation system, which is based directly on Debian, has had reproducible builds for a number of years now. [ ]

Lastly, Chris Lamb responded at length to a query regarding the status of reproducible builds for Debian ISO or installation images. He noted that most of the technical work has been performed but there are at least four issues until they can be generally advertised as such . He pointed that the privacy-oriented Tails operation system, which is based directly on Debian, has had reproducible builds for a number of years now. [ ]

If you are interested in contributing to the Reproducible Builds project, please visit our Contribute page on our website. However, you can get in touch with us via:

-

IRC:

#reproducible-builds on irc.oftc.net.

-

Twitter: @ReproBuilds

-

Mastodon: @reproducible_builds@fosstodon.org

-

Mailing list:

rb-general@lists.reproducible-builds.org

- Improve explanation how the status and scores are calculated. [ ][ ]

- Update and condense view of detected issues. [ ][ ]

- Query the canonical configuration file to determine whether a job is disabled instead of duplicating/hardcoding this. [ ]

- Detect several problems when updating the status of reporting-oriented metapackage sets. [ ]

- Detect when diffoscope is not installable [ ] and failures in DNS resolution [ ].

- Update the URL to the Debian security team bug tracker s Git repository. [ ]

- Reschedule the unstable and bullseye distributions often for the

arm64architecture. [ ] - Schedule buster less often for

armhf. [ ][ ][ ] - Force the build of certain packages in the work-in-progress package rebuilder. [ ][ ]

- Only update the stretch and buster base build images when necessary. [ ]

- Improve monitoring, such as number of mounts, disk, memory, etc.. [ ][ ][ ][ ]

- Install the

ruby-jekyll-polyglotpackage to needed for the recently-added internationalisation and translation support on the Reproducible Builds website. [ ] - Update link to report potential issues. [ ][ ]

- For Alpine and ArchLinux, make the cleanup routines in the event of an error more robust. [ ]

- Update the sudo configuration to permit Jenkins itself to unmount more directories. [ ]

- Setup automatic renewal of our Let s Encrypt certificates for all domains served by us (including

jenkins.debian.net,www.reproducible-builds.org,diffoscope.org,buildinfos.debian.net, etc.). [ ][ ][ ][ ][ ]

- Mark that the u-boot Universal Boot Loader should not build architecture independent packages on the

arm64architecture anymore. [ ]

If you think you know how to spread the word about reproducibility in the context of Bitcoin wallets through WalletScrutiny, your contributions are highly welcome on this PR [ ]Julien Lepiller posted to the list linking to a blog post by Tavis Ormandy titled You don t need reproducible builds. Morten Linderud (foxboron) responded with a clear rebuttal that Tavis was only considering the narrow use-case of proprietary vendors and closed-source software. He additionally noted that the criticism that reproducible builds cannot prevent against backdoors being deliberately introduced into the upstream source ( bugdoors ) are decidedly (and deliberately) outside the scope of reproducible builds to begin with. Chris Lamb included the Reproducible Builds mailing list in a wider discussion regarding a tentative proposal to include

.buildinfo files in .deb packages, adding his remarks regarding requiring a custom tool in order to determine whether generated build artifacts are identical in a reproducible context. [ ]

Jonathan Bustillos (Jathan) posted a quick email to the list requesting whether there was a list of To do tasks in Reproducible Builds.

Lastly, Chris Lamb responded at length to a query regarding the status of reproducible builds for Debian ISO or installation images. He noted that most of the technical work has been performed but there are at least four issues until they can be generally advertised as such . He pointed that the privacy-oriented Tails operation system, which is based directly on Debian, has had reproducible builds for a number of years now. [ ]

Lastly, Chris Lamb responded at length to a query regarding the status of reproducible builds for Debian ISO or installation images. He noted that most of the technical work has been performed but there are at least four issues until they can be generally advertised as such . He pointed that the privacy-oriented Tails operation system, which is based directly on Debian, has had reproducible builds for a number of years now. [ ]

If you are interested in contributing to the Reproducible Builds project, please visit our Contribute page on our website. However, you can get in touch with us via:

-

IRC:

#reproducible-buildsonirc.oftc.net. - Twitter: @ReproBuilds

- Mastodon: @reproducible_builds@fosstodon.org

-

Mailing list:

rb-general@lists.reproducible-builds.org

Start screen for the Wikipedia Adventure.

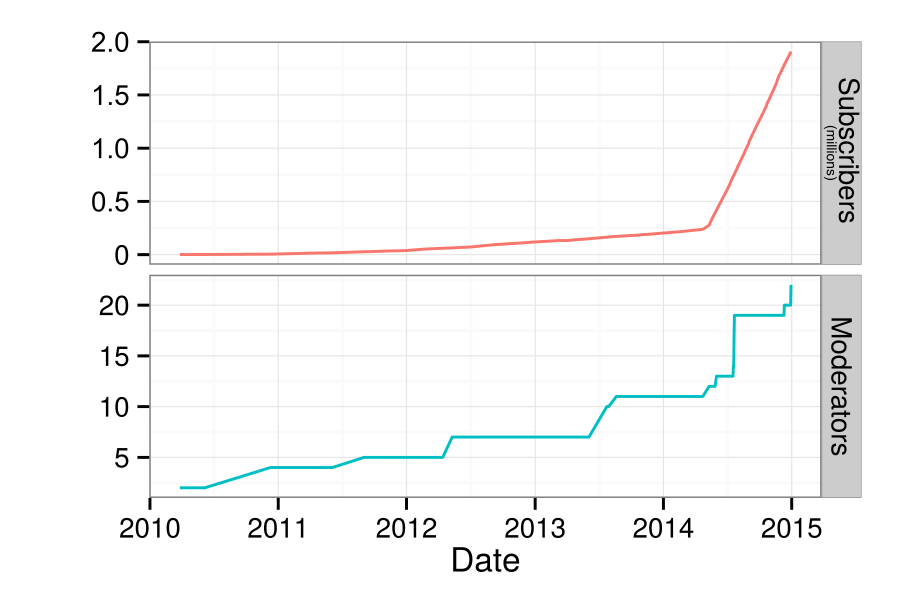

Start screen for the Wikipedia Adventure. The number of active, registered editors ( 5 edits per month) to Wikipedia over time. From

The number of active, registered editors ( 5 edits per month) to Wikipedia over time. From  An example of a badge that a user receives after demonstrating the skills to communicate with other users on Wikipedia.

An example of a badge that a user receives after demonstrating the skills to communicate with other users on Wikipedia. Survey responses about how users felt about TWA.

Survey responses about how users felt about TWA. Survey responses about what users learned through TWA.

Survey responses about what users learned through TWA.

Project metadata

Project metadata User metadata

User metadata Site-wide statistics

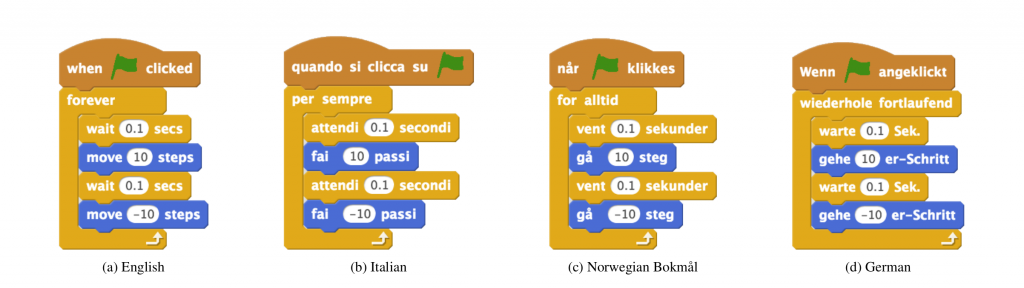

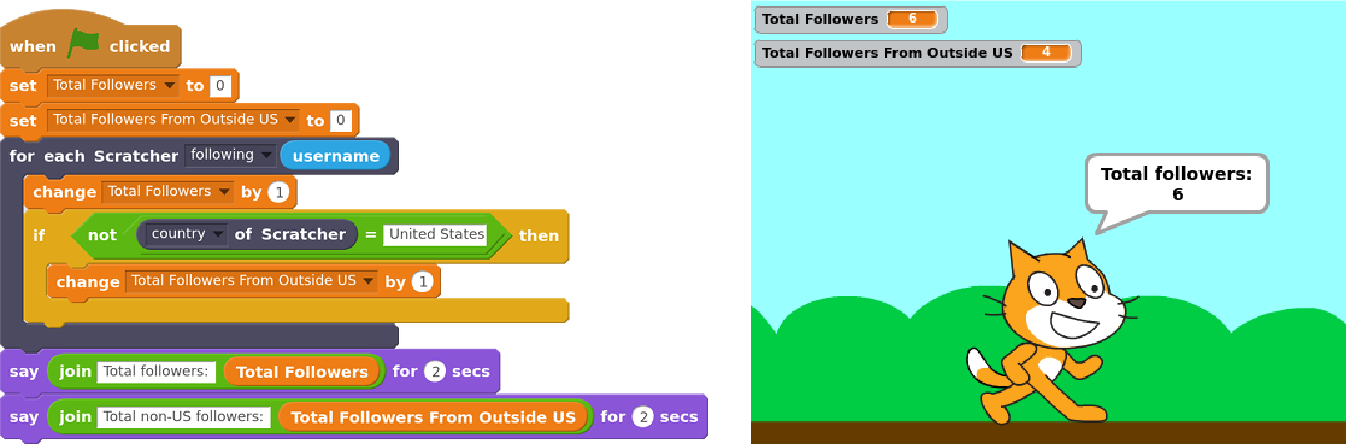

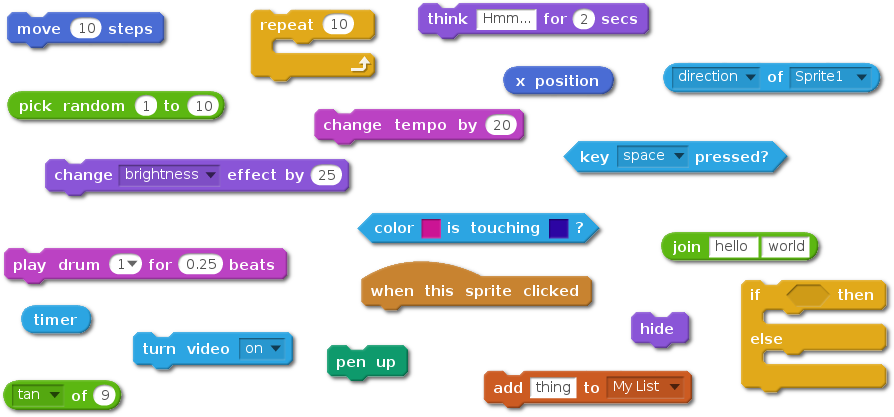

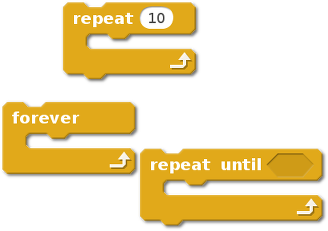

Site-wide statistics Simple demonstration of Scratch Community Blocks

Simple demonstration of Scratch Community Blocks Doughnut visualization

Doughnut visualization Ice-cream visualization

Ice-cream visualization Data-driven doll dress up

Data-driven doll dress up Like I wrote before,

Like I wrote before,  Earlier this week, I finally got my new machine that came with my

Earlier this week, I finally got my new machine that came with my

As some of the world knows full well by now, I've been noodling with Go

for a few years, working through its pros, its cons, and thinking a lot

about how humans use code to express thoughts and ideas. Go's got a lot of

neat use cases, suited to particular problems, and used in the right place,

you can see some clear massive wins.

I've started writing Debian tooling in Go, because it's a pretty natural fit.

Go's fairly tight, and overhead shouldn't be taken up by your operating system.

After a while, I wound up hitting the usual blockers, and started to build up

abstractions. They became pretty darn useful, so, this blog post is announcing

(a still incomplete, year old and perhaps API changing) Debian package for Go.

The Go importable name is

As some of the world knows full well by now, I've been noodling with Go

for a few years, working through its pros, its cons, and thinking a lot

about how humans use code to express thoughts and ideas. Go's got a lot of

neat use cases, suited to particular problems, and used in the right place,

you can see some clear massive wins.

I've started writing Debian tooling in Go, because it's a pretty natural fit.

Go's fairly tight, and overhead shouldn't be taken up by your operating system.

After a while, I wound up hitting the usual blockers, and started to build up

abstractions. They became pretty darn useful, so, this blog post is announcing

(a still incomplete, year old and perhaps API changing) Debian package for Go.

The Go importable name is  Started in 2008,

Started in 2008,